CAUSINDY Review

By the 2015 CAUSINDY Delegates

With our conference anchored in Indigenous culture, we collaborated with UTS:INSEARCH to run a series of writing workshops for our delegates. With the loose theme of ‘storytelling’, delegates were grouped together and tasked with producing a selection of pieces that reflected their experience of the bilateral relationship.

One day whilst two of the tribesman, Gurrumul and Alkira were out hunting for trepangers when they saw a strange looking ship on the horizon.

Gurrumul and Alkira rushed for their spears, ready to defend their country.

Where it all began

The shock of small boats on the horizon

Now coming ashore – strange men

Fear grips my country

They unload trepang on the beach

We watch from a veil of scrub

They are setting up camp

But when they leave a few weeks later

We have a new boat and new words

The next year they come back

And the next, and the next

One year he leaves with them

And never comes back

Group name: Paraikatte

“My earliest memories of Indonesia are of the smell of rice, sambal and belachan

(prawn paste) and hearing scattered words of Bahasa Indonesia being spoken (jelanas, makan, orang putih). For me it was normal to have many cultures in my family. For others, people thought it unusual. I grew up in Northern New South Wales but always had a strong sense of North Australian mixed identity. As I started going to at school, I found the that was history taught was disconnected from my family history. The concept of what it meant to be Australian, as presented in the media and in the stereotypes, did not fit me. After I graduated my education began. I read voraciously particularly on history I found the work of Henry Reynolds, Regina Ganter and Peta Stephenson helped me to put my story, my family story in a wider context of the multicultural North and hybrid Indigenous Asian communities. Through learning this hidden history set against the background of the White Australia policy, the Pacific Laborers act and the Aboriginal “Protector”, I returned to Indonesia in 2011 to visit family in Jakarta for the first time. My uncle showed me family photos. My Javanese and Malay ancestors who arrived in Darwin and on to Innisfail. In Innisfail they, like many Indonesians, became involved in the sugar industry cutting cane. I am only on the beginning on the journey of reconnecting with both my Indigenous and Indonesian heritage.”

Zach’s story not only highlights the historic links between Indigenous and Australian people but also reminds us of the depth of personal connections between Australians and Indonesians. Sometimes these experiences do not come to light unless those people are given the opportunity to reflect on their stories. When they do, all of these stories have something in common – a moment that sparked curiosity and a desire to learn more about our respective cultures.

Christian’s moment was watching Australian rules football for the first time at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. Coming to Australia on a university scholarship, he was working on a video project about the sport and elderly people in Australia. As he conducted interviews he was struck by the extent to which sport is a part of Australian life and culture. Even though Indonesia has more young people than Australia, sport is not a part of their life. Regardless of age, Christian could see that Australians were very appreciative of sport and the benefits it brought to their own health. Moreover, they were keen to talk about it to non-Australians – even without prompting.

Emma started going to Indonesia from a young age, and her first impressions were those of an unassuming child accepting as a normal part of her life visits to her father’s friends’ homes in the villages of Bali. During these visits she remembers playing with the children her age and walking through the rice fields with them. Even though their lives were very different and language was often a challenge, the nature of their interaction was genuine and without prejudice, and as children they could always find common interests and have fun together.

For Gabriel, his moment was one where he had the opportunity to spark curiosity in others about his culture. Having spent his high school years in Australia, Gabriel is a proud Indonesian who was given the opportunity to showcase his background to students during his school’s annual United Nations Day . Nasi goreng and satay were always the normal representation of Indonesia at this event, so he broke with this tradition by singing an Indonesian song while wearing a Batik shirt. Surprisingly to him, it was his Batik shirt that attracted the most interest, as few students had seen one before. In asking questions about Batik, the conversation that followed helped to take the understanding about Indonesia beyond nasi goreng and satay.

Before coming to Australia, Icha had previously only viewed the relationship through the lens of her work with the Indonesian government. Her studies at the Australian National University introduced her further to Australian culture and perspectives. She decided she needed to improve her understanding of Australian culture. In doing so, she was struck by the commonalities between Australians and Indonesians and that, ultimately, they were good people who were welcoming, tolerant and friendly. Through her alumni work she looked for opportunities to remind Australians and Indonesians that even though there are periods of tensions at the high political level there are always genuine relationships we can rely on.

When he took part in the Australia-Indonesia Youth Exchange Program, Ben’s first impression of Burno, the village where he lived in East Java, was of its poverty. Ben lived with a farmer who had paddy fields, and so in the mornings he would get up early and help him plant and cultivated paddy. There he realised that even though the family and the village was poor, for them, money was not important to them. The solidarity of the family and community that was more important. Contrasted with the situation in Australia where the social security system is provided by the government, he found that instead, Indonesia’s social security system was based on family and community, and that was where he truly understood the importance of that network.

Culture cannot be learned by reading a book alone, it has to be experienced. As former Vice President Boediono once said Indonesia and Australia are neighbours by destiny. Our connections run deep, but often those connections are forgotten when our countries focus more on our misunderstandings. Since the Macassan fisherman first began trading in northern Australia centuries ago, Australians and Indonesians have been building up a network of stories and relationships. It is important that we continue to look for more opportunities to build these connections, as these are the true bedrock of our relationship.

Spitting on a Muslim woman wearing a headscarf is usually a big cultural no no.

Ida Puspita from Yogyakarta, Indonesia, was happy to make an exception in the Northern Territory outback outside Darwin.

During a traditional welcome to country Aboriginal tour guide Deanne sprayed water from the billabong in her family's Limiangnan Woolna country onto the university lecturer's head.

The ritual was aimed at warding off bad luck and offering her spiritual protection from calamities such as snake bites or flat tyres.

"I am a guest in the other peoples' home so I have to respect their values," she said.

Ida's affinity with indigenous Australian culture grew out of reading the book Coonardo - a love story about the relationship between an Aboriginal woman and an Australian cattleman.

Ida moved to Wollongong, NSW in 2011 to study a masters in literature focusing on indigenous and Indonesian stories.

She sometimes found it difficult to connect with some Australians who struggled to understand her faith and decisions not to consume alcohol or eat pork.

Fear about terrorism attacks in the wake of the Bali bombings and September 11 was also a factor in people's prejudices, she said.

Ida has worn the jilbab since age 15 after making the personal choice to demonstrate modesty and have society respect her body.

"I feel that some Australian people see my hijab as a prevention for them to get to know me," she said.

"If they don't know me how can they judge?"

It was through the medium of Aboriginal art that Ida decided to express her experience of being a Muslim Indonesian woman living in Australia.

She won a competition to be part of an ABC documentary 'My Australia' where she met two Indigenous artist sisters Lorraine and Narelle.

Together the trio created a painting and bonded over shared experiences of prejudice, racism and being labelled with unfair stereotypes as members of a minority group.

"I think we've got an understanding of what she's going through," Lorraine said.

The artwork now hangs proudly on Ida's lounge room wall in Yogyakarta - a daily reminder of the comfort she found in friendship, in the land of the kangaroo.

"I feel empathy and solidarity with the first Australians," Ida said.

Lisa Martin

AAP journalist

+61 2 62712321

+ 61 419571480

Leaving I’m standing on the shore Where it all began

The shock of small boats on the horizon

Now coming ashore – strange men Fear grips my country

They unload trepang on the beach We watch from a veil of scrub

They are setting up camp

But when they leave a few weeks later We have a new boat and new words The next year they come back And the next, and the next

One year he leaves with them And never comes back

Pesan dari Darwin

Untuk kalian semua

Rasalah rasa ingin tahu

Bertanyalah dan buka

Cara pandangmu

Carilah cara untuk berbaur

Dengan budaya

Alamilah untuk mengerti

Tetaplah berfikiran yang terbuka

Hormatilah

Semoga kamu menemukan

Kejutan yang menyenangkan

An unexpected gathering Dawn in a hotel room

Mid-week, the holy month Strange birds squawk and bicker outside I miss home and family I pray - but my mind wanders back to them

Later I leave the conference estranged And wander by the lakeshore to find peace A raucous gathering in the gardens disturbs me But when I peer through the trees I can see People of different faiths

Celebrating Idul Fitri And they embrace me Lost and found Lost in the streets of a foreign city I walk by a muddy riverbank, I catch a tram I have no idea where I am I let go and see where it takes me In the backstreets off Brunswick street Beneath a sky of crystal blue

In a market I find my muse A ring made of an a old twisted spoon The faded emblem of the city

Makes for a time-worn face

And I make a pact:

Let this be my compass Something on which to hold fast

Saatnya pulang

Mamaku yang tercinta

Nenekku yang tersayang

Saudaraku yang terkasih

Indonesia yang istimewa

Tanah yang bukan tanah airku

Tidak kulupakan

Keluarga yang bukan keluarga kandungku

Tidak kulupakan

Untuk selamanya

Thanksgiving

Terima kasih

Atas ilmu dan kesempatan

Terima kasih

Atas tawa dan canda

Terima kasih

Atas persahabatan

Yang telah diberikan

Hubungan dan perjalanan kita

Bukan waktu yang sebentar

Tapi cerita kita hanya awal

Bukan akhir

Homecoming I can see it now, my home The turquoise saltwater coast That muddy shore I left so long ago Will she be waiting for me? In my bag is a knitted cap I know their prayers and I bring their words I have so much to tell my people

Group 2

Dreamtime Story: Komodo and Crocodile

Long ago in the Dreamtime, the Yolngu people lived a peaceful life by the sea.

One day whilst two of the tribesman, Gurrumul and Alkira were out hunting for trepangers when they saw a strange looking ship on the horizon.

Gurrumul and Alkira rushed for their spears, ready to defend their country.

But when the ship came ashore, they were greeted by the Smiling Man.

Gurrumul asked in his native tongue, “Who are you and where do you come from Smiling Man?”

But the Smiling Man could not understand. Instead he just smiled and offered them some fresh fruit. They had never seen fruit like this before; bright purple, shaped like a star and delicious.

While Gurrumul and Alkira were enjoying the starfruit, they heard a strange hissing sound coming from the boat. When they looked up, they saw a funny looking land crocodile running straight for them and baring his poisonous teeth.

Alkira yelled “Crocodile” in his native tongue and raised his spear, ready to strike.

But the smiling man signaled “STOP” before pinning the goanna down with a “Y-shaped” stick

While the beast lay quietly in the sand, the Smiling Man pointed and said in his native tongue “Komodo”. Gurrumul and Alkira responded with “Ahhh Komodo!”

Gurrumul and Alkira were so grateful that they signaled to the Smiling Man to join them and the rest of their tribe for a feast of trapanges.

As they crossed the river back to their camp, a giant crocodile swam towards the Smiling Man.

The Smiling Man yelled “Komodo” and pointed his y-shaped stick but the crocodile snapped it with his mouth in one bight.

Alkira leaped towards the crocodile and stuck his finger in the crocodile’s eye. The crocodile left the Smiling Man alone.

Smiling Man said in his native tongue “Thank you for saving me from the Komodo!” To which Alkira pointed and said ”Crocodile”. The Smiling Man said “Ahhhh Crocodile!”

They arrived at camp with exotic fruit, a new friend, a new language and all of their limbs.

Kelompok 2

Cerita Anak-anak: Komodo dan Buaya

Dahulu kala di negeri antah berantah, orang-orang dari suku Yolngu menjalani kehidupan dengan tenang dan damai di pinggit laut.

Pada suatu hari ketika dua orang dari suku tersebut yakni Gurrumul dan Alkira sedang berburu teripang, mereka melihat sesuatu yang aneh yakni kapal di tengah lautan yang datang mendekat.

Gurrumul dan Alkira segera mengambil tombak mereka dan siap melakukan perlawanan untuk mempertahankan tanah mereka jika ternyata ada ancaman yang datang. Tetapi ketika kapal semakin mendekat dan akhirnya berlabuh di pantai, justru mereka disambut oleh wajah-wajah yang murah senyum dari orang-orang yang menaiki kapal tersebut.

Gurrumul bertanya dalam bahasa daerahnya: "Siapa kamu dan darimana kamu datang wahai orang-orang yang murah senyum?"

Orang-orang yang disapa itupun tidak bisa mengerti apa yang dimaksud oleh Gurrumul dan Alkira. Sebaliknya, mereka hanya menjawab dengan tersenyum dan menawarkan buah-buahan segar untuk Gurrumul dan Alkira. Ternyata buah-buahan yang diberikan itu belum pernah dilihat sebelumnya oleh mereka. Buah-buahan itu berbentuk seperti bintang, berwarna ungu terang dan sangat lezat. Buah itu adalah Belimbing.

Sementara Gurrumul dan Alkira sedang menikmati belimbing, mereka mendengar suara mendesis yang datang dari dalam perahu.

Ketika mereka mencari sumber suara itu, mereka melihat “buaya darat” yang lari kearah mereka sambil memamerkan gigi dan lidah beracun nya. Alkira berteriak "Buaya" dalam bahasa asli mereka sambil mengangkat tombak dan siap untuk menyerang.

Tetapi orang-orang yang datang dari kapal itu memberi isyarat untuk "BERHENTI" sebelum akhirnya menjepit leher binatang itu dengan tongkat kayu.

Sementara binatang itu berbaring diam di atas pasir, orang-orang dari kapal itu menunjuk dan berkata dalam bahasa asli mereka "KOMODO". Gurrumul dan Alkira menanggapi dengan berkata: "AHHH KOMODO!"

Gurrumul dan Alkira sangat bersyukur dan akhirnya mereka member isyarat kepada orang-orang dari kapal itu untuk bergabung dengan suku mereka untuk pesta dengan memakan trepangers.

Saat mereka menyeberangi sungai untuk kembali ke perkemahan mereka, buaya raksasa berenang menuju orang-orang kapal itu.

Orang-orang kapal itu berteriak "KOMODO" dan berusaha untuk menjinakkan binatang itu dengan tongkat kayu yang mereka bawa, tetapi tongkat kayu itu dipatahkan hanya dalam satu gigitan.

Alkira melompat ke arah binatang itu dengan mencolokkan jarinya ke mata binatang itu. Akhirnya binatang itu pergi meninggalkan orang-orang kapal.

Orang-orang kapal yang murah senyum itu berkata dalam bahasa aslinya: “Terima kasih karena telah menyelamatkan kami dari Komodo!". Alkira menunjuk dan berkata "BUAYA". Orang-orang kapal pun menjawab: "Ahhhh Buaya!"

Akhirnya mereka tiba di perkemahan penduduk asli sambil membawa buah-buahan yang enak, teman baru, bahasa baru dan badan yang utuh selamat dari gigitan Komodo dan Buaya.

***

Australia and Indonesia: the Paradox of Communication

The command of language is central to effective communication. The ability to communicate with languages makes humans such complex creatures. However, sharing a common language itself isn’t tantamount to understanding.

Comparing between now and the ‘distant’ then, a paradoxical logic exists in how Australia and Indonesia communicate with one another. Before the European colonisation of Australia, the Yolngu Aborigines and Indonesians, referred to as the Macassans, couldn’t effectively communicate due to the absence of a common language, yet they could mutually understand one similarity: the ocean was key to their survival. History attests their harmonious co-existence in sharing the ocean resources in Australia’s north: the Macassans collected sea cucumber and other marine resources, while at the same time, transferred maritime knowledge and technology to the local indigenous Australians.

Today, politicians in both Jakarta and Canberra like to emphasise the importance of communication in the bilateral relationship. We can now effectively communicate in English and for some Australians, in Bahasa too. Yet whenever we talk, we often talk past each other. As such, our present relationship is prone to misunderstanding.

Why does such a paradox exist? It’s a choice to either underscore our differences, or cherish our similarities. When we fix our attention to the former, our worlds are poles apart. Yet our similarities compel us to bridge those differences. Not only do we share the same geographical space, but we also maintain a common desire to live in a stable and peaceful neighbourhood, address shared security challenges, and improve the welfare of our peoples. In doing so, we need each other much more than we are currently willing to acknowledge.

This is what we learned from CAUSINDY, a conference bringing together Australian and Indonesian youth held in Darwin in September 2015. At CAUSINDY, we were reminded about the enduring ties between the two traditional communities who preceded the birth of our nation-states. If they could co-exist harmoniously in the past, why can’t we today, despite a common language? Our nations will never be identical. Clashes of interests and disagreements will emerge from time to time, but we must ensure that we can bridge those differences amicably, both in practice and rhetoric.

The key to bridge those differences is empathy: the ability to read the thoughts and share the feelings of others. We may strongly disagree with one another, but we should mutually understand why we disagree. It’s disappointing to see that only 33% of Australians regard Indonesia as a democracy, according to the 2015 Lowy Institute Poll. This demonstrates that we don’t only share a common desire, but also a common enemy: ignorance.

Ignorance is a perfect recipe for misunderstanding. Without effective communication, a stereotypical, biased, and bigoted view of an ignorant public can be used or misused by anyone to achieve their narrow political objectives, but we’ve pledged to never tolerate this.

Representing the young generations of Australia and Indonesia, the worst thing we can do is nothing. In today’s world, a common language is not sufficient to generate a mutual understanding. We need shared experiences, good or bad.

Darwin gave us one invaluable experience: how similar our nations are, despite our differences. We essentially desire the same things, although we sometimes clash in trying to get them. In Darwin, we learned about the importance of language to communicate our differences as friends, and not rivals. In Darwin, we were strangers at first, but mates in the end.

END

Capturing the personal element of surprise between Indonesia and Australia

CAUSINDY Review 2015

Typically, it is the misperceptions and missteps between Indonesia and Australia that make the news. But if you look beyond this apparent disconnect, Australians and Indonesians often find they have more in common than they think. In fact, the rich exchange between both communities goes back well before the founding of our two modern nation states.

Over four days in September 2015, a group of thirty young Indonesians and Australians gathered in Darwin for the Conference of Australian and Indonesian Youth or CAUSINDY, now in its third year. They explored the shared and complex histories, contemporary politics and trade between the two countries.

Participant Feliciana Natali Wienathan is a young entrepeneur who came to Australia in 2008. She founded and is now head of marketing for Eagle Group Indonesia, a company based in Jakarta.

Felicia explains how she was lost in the streets of Melbourne when a shopkeeper offered her a ring made from an old spoon, carrying the City of Melbourne coat of arms.

“From the moment I found this vintage ring amongst the fashionable Rose Markets in Melbourne, I realised how much creativity Australia had to offer.”

Felicia then decided to pursue a Masters degree at Monash University and now feels she has a lifelong affinity for Australia and its people.

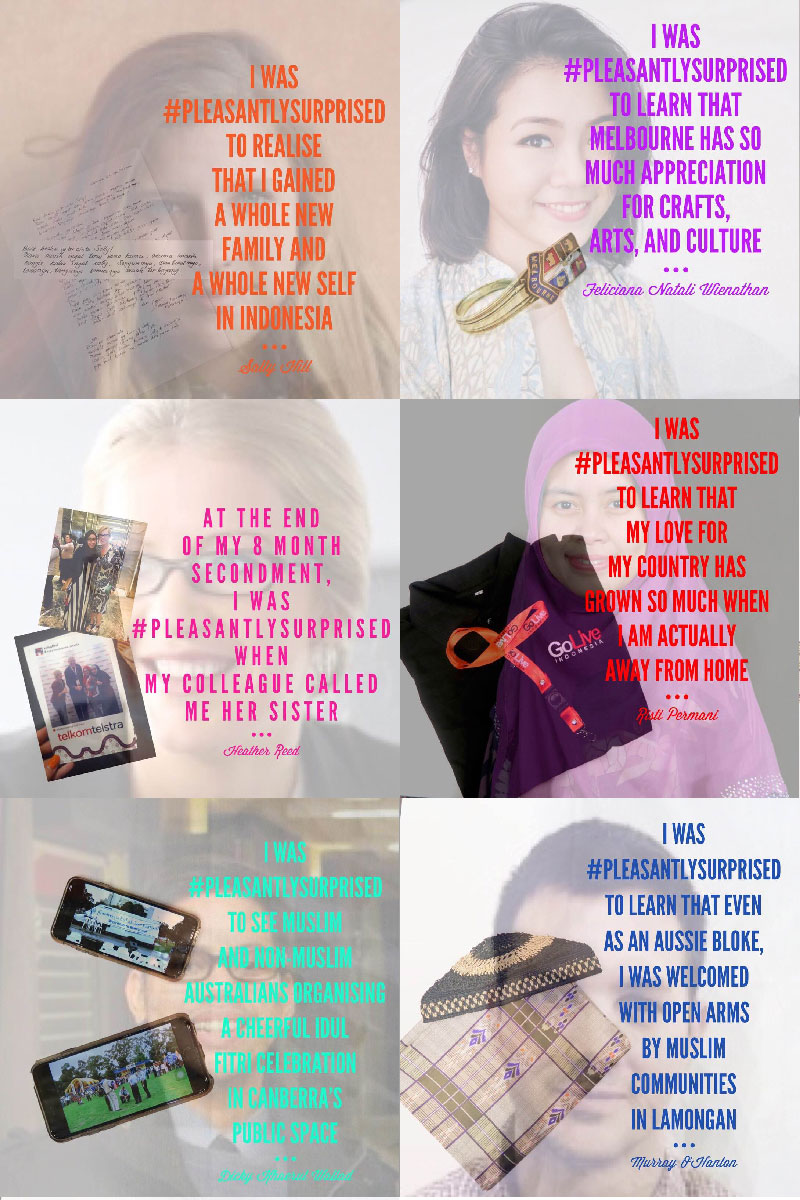

During CAUSINDY, Felicia and her colleagues created a series of internet memes to capture these moments of surprise and relate them back to specific objects that reminded them of the Indonesia-Australia relationship. You can share the memes from this Facebook page.

Sally Hill works at law firm Minter Ellison and is organising Australia’s first comprehensive speaking competition for students of Indonesia. Sally has spent the last eleven years traveling between Australia and Indonesia for work, study and to visit a host family in Lombok.

“My aunty travelled to Lombok around thirty years ago and made friends with a family who live near Mount Rinjani, one of Indonesia’s largest volcanoes. On my first visit to Indonesia she took me to visit them.

“I can still remember the smell of the country as I first stepped off the plane: it was frangipani. I was young, impressionable and had no idea what to expect.

“Cultural blunders and daily teachings were my staple diet. But I found out more about myself, and I found myself adopted by this family too.

“Last year I travelled to Lombok again for a wedding - it was the first time that my immediate family and my host family were all in the same place at the same time.

“It’s an extraordinary gift to have two families in two countries.”

DK Wallad first visited Australia in 2011 and until recently was living in Melbourne. He graduated in August 2015 with a Master of International Relations from the University of Melbourne.

DK recounts his accidental discovery of Australia’s Islamic community during Eid al-Fitri (usually rendered Idul Fitri in Indonesian).

“I was travelling to a conference in Canberra and was sad to be away from my family during this special time. Eid is that time when all the family is together, so it’s just like how Aussies would feel if they were missing out on the family Christmas at home.

“After breakfast I decided to explore the city. I stumbled across thousands of people, probably half of Canberra. Muslims and non-Muslims were all celebrating Idul Fitri.

“It was surprising because I just didn’t realise that Australians also recognised and celebrated Eid together.”

Earlier this year, Heather Reed, marketing implementation lead for Telstra, helped establish a joint venture with Telkom Indonesia. She developed the marketing strategy for the initiative and was a mentor for the new team.

“On day one of an eight-month stint in Indonesia, a long way from my family and friends, I found myself greeted with the loudest ‘Selamat Pagi’ or good morning.

“From that moment I knew I’d be just fine.”

Heather was surprised at the efforts that Australians and Indonesians in her team made to break down cultural barriers - with all the Aussies wearing traditional batik shirts to a team lunch, while the Indonesians wore full western suits and ties.

Risti Permani, a young researcher and academic from the West Java hill town of Bogor, has been based at the University of Adelaide since 2004. She developed a strong working relationship with her professor, who introduced her to former Indonesian trade minister Mari Pangestu - herself an alumnus of an Australian university.

“When I arrived in Adelaide I was surprised to find so many similarities with my home town, Bogor.

“Both have beautiful botanical gardens and a similar-sized population. But most importantly, I feel at home in both cities.”

Risti and her professor have developed an initiative called ‘GoLive Indonesia’ to promote greater economic integration between Australia and Indonesia.

With few opportunities to study Asian languages in his rural high school, Murray O’Hanlon wanted to start at university. He chose Indonesian after meeting a diplomat who had been posted to Jakarta and Dili.

Murray enrolled in Indonesian Studies in 2002. Like many young Australians his first travel experiences were to Bali and Lombok, where he hiked the spectacular Mt Rinjani. In 2005 he joined ACICIS, the major Australia-Indonesia exchange program, and completed a research semester in East Java.

He recalls how his experiences opened his eyes to the diversity of religious communities in Indonesia.

“Around the time of the second Bali bombings I was studying in East Java. I planned to research the area where the Bali bombers had come from, to understand more about the world views of communities in places like Lamongan.

“Like most Westerners who have visited these areas, I found that extremism represented a tiny fringe, a cult-like element far outside the mainstream of society.

“Locals were apologetic and embarassed about what their neighbours had done in the name of Islam. ‘It’s ruined the reputation of our district’ they would say.

“What most surprised me was how readily my host family treated me - a non-Muslim - like their own son.

I remember taking my friend Ghozi to watch Christmas carols at the beautiful Catholic church in Malang. Ten years later we still have a lasting friendship.”

Conference participants get a unique version of ‘welcome to country’

This year CAUSINDY was centred around the shared history between Australia and Indonesia. Panel sessions looked back to the earliest exchanges between the Larrakia and Yolngu people of the Top End, and the Macassans (a term covering the seafaring Bugis, Makassarese, Madurese, Javanese and other groups from Southeast Asia) who sailed to Arnhem Land for pearls and sea cucumber.

Evidence of this exchange dates to the early 1700s, with up to a thousand visitors each year travelling to northern Australia for seasonal fishing, referring to the Kimberley and Arnhem coasts as Kayu Jawa and Marege. Aboriginal people of the north also travelled back with Macassans into Southeast Asia.

During the conference, participants visited the Adelaide River outside Darwin to watch crocodile feeding, and they received a welcome to country from Deanne, a local Larrakia woman.

Standing on the edge of a picturesque billabong on her mother’s lands, known as Limiangnan, Deanne explained the idea behind the welcome to country.

“It’s a sign of respect to the local people and to the land. It’ll keep you from harm while you’re travelling through, whether from spirits or any other kind of danger.

“The welcome to country can be dance, music, or just a few spoken words. But our dreamtime story is tied to the water. So we are going to put some water on your head as a sign of welcome to country,” she said.

It was clear something special was in store as Deanne and her sister held back laughs and reached towards the bucket of water at their feet.

“So now just line up in twos… and we’re going to spit this water on your heads.”

Participants exchanged nervous looks but dutifully lined up, while the two young Larrakia girls took turns in spitting out great bursts of water over them.

Ida, a young Muslim girl from Java’s cultural heartland of Yogyakarta (wearing a bright red hijab at the time) quipped:

“Normally if a Muslim girl in a headscarf is being spat on it would be considered extremely rude - but I was happy to experience the local people’s way of welcoming a stranger to their land.”

Felicia was captured taking a selfie while being welcomed in this this fashion. You can see the photos and a video of Ida on the CAUSINDY Instagram website.

Participants took part in seminars with prominent academics, and shared meals with resident territorians, including members of parliament and Indonesian Consul-General Andre Omer Siregar.

Participants to publish wide-ranging works on the Aus-Indo relationship

During the conference, teams worked around the clock to produce three publishable works in visual, written and performance media.

Team Three tackled the ‘surprise factor’ in Australia- Indonesia relations, and as the participants shared their stories it became evident their suprise discoveries were overwhelmingly positive.

They developed a series of memes, wrote this op-ed you are reading now, and wrote a poetry cycle, imagining pre-European contact between the Macassans and Aboriginal people, linked to their own moments of discovery. They recited the works on the final day of the conference.